Cultural Production

Hanne Darboven, Josephine Meckseper, Allen Ruppersberg, Alexandre Singh

February 11 – March 24, 2012

Main Gallery

Opening reception: Friday, February 10: 6-8 p.m.

Andrea Rosen Gallery is pleased to announce the exhibition Cultural Production, featuring work by a multigenerational selection of artists including Hanne Darboven, Josephine Meckseper, Allen Ruppersberg, and Alexandre Singh. The works included demonstrate a conceptual art practice that is mapped out and then (re)framed within the context of an installation. In these arrangements, everyday objects and techniques of mass production are integrated and subverted, permitting the inclusion of the audience in the process of decoding the propagandistic diversion inherent in art-formalized language constructs. The works in this exhibition all display an economy of materials to broaden the scope of what art can be and what it can hope to achieve. As Darboven said in 1968, "I like the least pretentious and most humble means, for my ideas depend upon themselves and not upon material; it is the very nature of ideas to be non-materialistic."

Darboven's accumulative, all-encompassing work and her role as one of the founders of conceptual art makes her a cornerstone of this exhibition. Darboven frequently combines the form of the grid with typewritten or handwritten numbers and text. Darboven's work, however, resists a reading that is entirely rational and impersonal and subversively implies the vast complexities that lie hidden behind forms that project neutrality. For example, in perhaps her most famous work, the Kulturgeschichte 1880-1983, 1980-83 Darboven incorporates selected pages from the news magazine Der Spiegel and in this way compares the historic importance of the Enlightenment in Europe to the regressive and catastrophic consequences of fascist Germany. The monumental work in this exhibition Webstuhl postrum, 1997 is comprised of 192 sheets of yellow graph paper. The sheets are organized into twelve grids of 16 sheets, corresponding to the months of the year with each grid featuring a black and white image of a loom from Darboven's childhood. The image of the loom and its connotations to labor, gender, and automated process subtly and radically ruptures the work's immediate reception as simply a kind of calendar or inventory of the passage of time. Similarly, while each artist in the exhibition has a unique practice and while these works are incredibly diverse both formally and conceptually, it is compelling that each artist broadly addresses how a categorization of material can paradoxically generate more information rather than a simplification through didacticism.

Meckseper's work melds the aesthetic language of modernism with a profound critique of consumerism. Her practice can be described as broadly conceptual, but crucially two later offshoots, appropriation art and institutional critique, are at the heart of her work. Meckseper employs window displays, vitrines, installations, photographs, films and magazines to explore how consumer culture defines subjectivity. In her vitrines, which function like shop window displays, the unsettling combinations of objects and materials create a melancholic atmosphere alongside allusive materialism, political process and propaganda. The industrial slatwall functions like a minimalist painting—its built-in horizontals echoing the purity of Agnes Martin, while simultaneously being a readily available vehicle for product display. Much like the other artists in the exhibition, Meckseper's incredibly considered selection and placement of objects has the effect of turning these common consumables into something strange and uncanny so that their values and hidden agendas are both revealed and undermined.

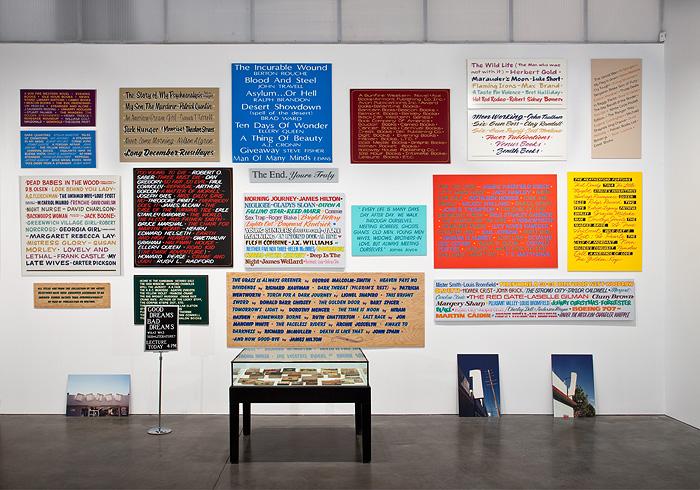

Ruppersberg's work in this exhibition Good Dreams, Bad Dreams, What was Sub-Literature?, 1996 is comprised of panels painted by professional sign painters, four photographic panels, a sign board, and a vitrine filled with popular literature. This work encapsulates many issues that have remained at the core of Ruppersberg's practice since the 1970s: an interest in the multiple and the original, reading, narrative, and collective cultural memory. While seemingly quite specific about the subject of pulp fiction, Ruppersberg's very personal system of categorizing the titles of the books allows a viewer to begin to narrate his or her own understanding of the work's larger meaning. In this collection of objects, American's cultural preoccupations, neuroses, and desires become subtly manifest. Ruppersberg is one of the most important figures to emerge from the conceptual art movement associated with the California Institute of the Arts in the 1970s, and his work has consistently worked to bridge the divide between art experience and the quotidian experience of the world.

Singh's work Assembly Instructions (Concerning the Apparent Asymmetry of Time: Painting), 2010 is comprised of 37 framed inkjet collages connected by a wall drawing of dots. The work imagines a narrative of modern art if the second law of thermodynamics has been reversed; if, instead of a movement towards entropy, there would be a tendency towards order. The resulting story appears as a complex flowchart, which belies its pedagogical function through the subtle inclusion of humor and absurdist wit. While the Assembly Instructions take the form of wall installations, they are exemplary of Singh's practice, which includes performances that often take the form of wildly expansive lectures blending fact and fiction or his sculptural installation The School of Objects Criticized, 2010 comprised of mundane objects on pedestals performing a theatrical play. Singh's work interrogates the authority of academic discourse and representation, systematic aesthetics, and historical narrative. Like the other works in the exhibition, regardless of medium, Singh's work shows the way that language and ideas can mutate and change over time.

"Action interrupts contemplation, as the means of accepting something among many given alternatives," Darboven wrote, "for accepting nothing becomes chaos." This exhibition ultimately examines the role and responsibility of artists to marry intellectual discourse to an open ended experience and asks: How does one reconcile the symbolic and monetary values of cultural production? How does one make visible real economic and political realities without just mimicking them? Is there a way to reveal the complex systems and structures that subtend everyday life? And finally, is there still a subculture or subversiveness in art at all?

For images and press information please contact Jessica Eckert at j.eckert@rosengallery.com