Andrea Rosen Gallery is pleased to present a solo exhibition by Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin, the first at the gallery since announcing its representation of the artists in 2012. Over the course of the last three years, the artists have created several expansive bodies of work—encompassing single and multi-channel videos, large-scale installations, and densely layered soundscapes—which have been exhibited at important institutions internationally. Such institutions include the 55th Venice Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, MOMA PS1, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Continuing the long-standing collaborative approach to their work, for the current show in particular, Fitch and Trecartin have collaborated with Rhett LaRue, who has been deeply involved in the production and post-production aspects of this project.

For this occasion, Los Angeles–based writer Kevin McGarry has written an introduction to the exhibition:

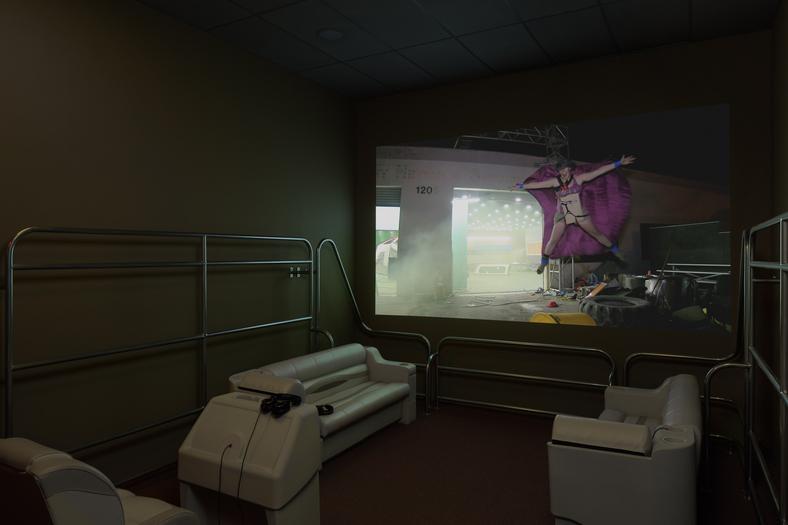

Furthering their notion of “sculptural theaters”—installations built as containers for specific movies, whose architectural, audiovisual, and sculptural elements expand onscreen content into environmental panoramas—the artists have transformed Andrea Rosen Gallery into a network of halls and chambers that plot a path for visitors through a sequence of new movies and ambient spaces.

The thematic language of these enclosures is lifted from lakeside Americana—nature as retreat. One room is distinguished from a placeless labyrinth by the railing of a pontoon boat that snakes around its perimeter; another is floored with pine 2x4s resembling a dock. The movie looped in this room is projected beyond the edge of the planks, above a shallow drop into a carpeted void simulating water. Elsewhere, seating is carved from foam, tromp l’oeil boulders. The entire space is bound together by an atmospheric composition of nature sounds largely produced by an online sound generator, instilling a kind of numbed, placid continuity.

These rustic cues are a departure from generically slick, suburban merchandise shopped from international retailers, the likes of which the artists are best known for casting as furnishings for their installations. But the great outdoors is the jurisdiction of only another department in the same type of store, whose all-purpose ubiquity reflects the comfort cravings of the American psyche.

This new body of work is a continuation of ideas and characters introduced in two recent bodies of work: Priority Innfield (2013) and Site Visit (2014). In the four movies that comprise Priority Innfield, humanity is relegated to the structures of gaming with characters operating more like players or proxies in a networked system organized by levels. Site Visit is a young adult horror-movie-type group expedition filmed in the former Wilshire Boulevard Scottish Rite Masonic Temple as a kind of campsite wasteland.

As they have in other recent works, members of a production apparatus carrying lights and cameras and uniformed in sweatshirts with the word “WITNESS” emblazoned in blocky collegiate type circle the protagonists of the new movies, documenting and sometimes directing their behaviors. The most frequently occurring star is Mark Trade (played by Murphy Maxwell), a volatile, straight-shooting, long-haired hick-sage whose wardrobe is a medley of specialty items designed for hunting, extreme sports, and the 4th of July. In previous works, Trade has performed as a kind of host presiding over situations that mimic reality competitions. Here, his cadence is modified; instead he shifts between modes of different types of traditional presenters, riffing on the canned intimacies of a meteorologist or Public Service Announcement personality, for example.

The scripts are complicated by performative flourishes that echo the capture of real life. Much of this is owed to riveting non-actors like Maxwell, but also to the conditions, often durational, set forth and adhered to by the entire cast and crew. In this case, many scenes in the new works were filmed during a road trip from California to the American heartland, through mystical canyons, abyssal salt flats, and a forest glade built around a bonfire. These new settings, nakedly undeveloped, introduce new forms of intimacy between actor and camera. At times this dynamic plays out at a distinctly decelerated pace, via wandering monologues, and at other times Trecartin’s signature style of merged narratives and perspectives compound upon one another as multisensory cacophony.

Ruralness emerges as a motif, which has only been contrapuntally incorporated into previous works through moments in cornfields or vacation spots similar to the ones here. The exception is the movie from Priority Innfield called Junior War—culled from dozens of hours of 1999 footage Trecartin shot while an Ohio high school student—whose lo-fi, green-scale night vision aesthetic is misleadingly reproduced here in scenes shot in the present day. This gambit chips away at how time and reality have otherwise been compartmentalized throughout the oeuvre via production and post-production technologies that epitomize their zeitgeists.

The barrenness that tracks throughout these new movies evokes a dream-like “post-apocalyptic” sense looming in popular consciousness, though truer to the work than any evidence of a major event is the absence of people. In this sense, the language that panders to a docile audience—“Back to you, Monica!” at the close of a stream-of-consciousness pseudo-broadcast—is addressing an audience that is not actually there. It’s creepy, haunted, a vacuum of pretending that often reverberates as uncanny, which heightens the disconcerting feeling of being temporally located “after" something world-changing, without any indication of precisely what that might be, or even if that “something” is real at all, and not a video game-like premise, with no connection to the causal relationships of actual time. Characters seem to appreciate solitude as luxury, a remnant from societies of overstimulation. Their purgatories become pleasurable recreational zones—being stuck becomes a platform for practicing stunts, for squandering their human thresholds.

The prevailing genre of this entire body of work is horror, capitalizing on bottomless sensations of suspense and sorrow. There have always been dark undercurrents to Fitch and Trecartin’s installations and movies, a disquieting humor in the earliest works that evolved into the outwardly sinister face of Any Ever. The new movies fall deeper away, where menace becomes mourning, plumbing loneliness and sadness to explore their contemporary mutations with existential wit. A hallmark of Trecartin’s videos: a masterful exploitation of cinematic unities and dislocations conjures a world that evinces a unique emotional logic that is as ineffable as it is irrepressible. “Everyone is stuck in modes of anticipation,” Trecartin says—“or recollection,” adds Fitch—“They’re either remembering or foreseeing, but no-one is actually having experiences. There’s a fear of being.”

Lizzie Fitch (born 1981 in Bloomington, Indiana) lives and works in Los Angeles, California.

Ryan Trecartin (born 1981 in Webster, Texas) lives and works in Los Angeles, California.

Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin have been working together since they met at Rhode Island School of Design in 2000. Since then, their work has been included in exhibitions at major institutions around the world, including: La Casa Encendida, Madrid (2016); KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2014–15); the Venice Biennale (2013); Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris (2011–12); MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York (2011); and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2006).

For media inquiries, please contact Justin Conner at justin@hellothirdeye.com

Download PDF